Jane Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice” opens with the sentence, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” It is one of the best written and best known opening lines of any novel. It is also one of the best examples of “comic irony” because, as Austen makes clear throughout the novel, it is primarily the women (or more particularly their mothers) who are desperately in search of a rich single man as husband-material.

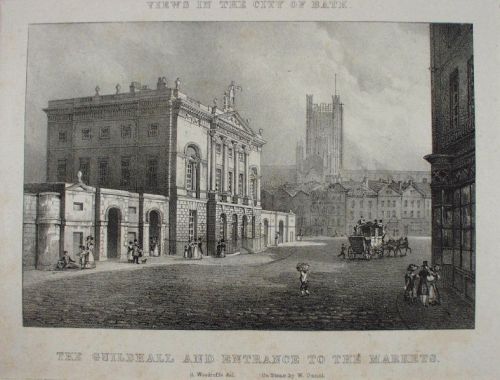

Historically Bath was undoubtedly one of the most favoured locations for such match-making, both in fact and in fiction. Though the city is relatively small today, it had grown faster than almost any other in Britain during the 17 th Century. In 1801, when Jane moved to the city it was the ninth largest conurbation in England with a population of 35,000. Its spa facilities and entertainments were renowned throughout Europe and visitors flocked to the city for “The Season” (roughly from the beginning of May to mid-September). This was the ideal time for husband-hunting.

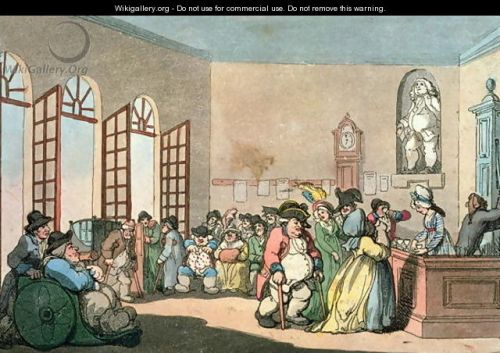

There were balls and gatherings, concerts and card games in the Upper and Lower Assembly Rooms. Each day people met in The Pump Rooms (see Rowlanson’s image above – Wikimedia) to see who was newly arrived in the city, to make introductions (and to be introduced) and perhaps most importantly to exchange gossip, and arrange social events. The theatre too, was well attended with a continually changing programme of popular contemporary productions, drawing some of the finest actors and performers of the age.

People also entertained at home, and yet one of the most favoured social events (weather permitting) was simply “promenading” in the popular shopping areas like Milsom Street, or the many purpose-built, Parades and Parks, like Jane’s favourite, Sydney Gardens. These were the places to see and be seen, the places where accidental meetings might be expected, or could be contrived. As Catherine Morland remarks in “Northanger Abbey”

“a fine Sunday in Bath empties every house of its inhabitants, and all the world appears on such an occasion to walk about and tell their acquaintance what a charming day it is.”

It would be easy to be swept away by images of “beautiful people” in a social whirl of high society events, set against a back-drop of some of the finest Georgian architecture in the world. Indeed that is the world that Jane Austen seems to present in her novels, yet that was not the whole truth, at least for Jane. The notorious British weather certainly often made promenading, or even attending events or visiting friends, difficult. As Jane said in a letter to her sister, Cassandra,

“We stopped in Paragon (a prestigious address where her wealthy uncle lived) as we came along, but it was too wet and dirty for us to get out.”

It must also be remembered that Jane lived in Bath continuously (throughout the years) from 1801 to 1805, and the city was a very different place, out of Season. Being primarily a Spa, many of the resident population of Bath were of retirement age and not always in the best of health. As for eligible young men, only 39% of Bath’s population were male in 1801, and it is safe to assume that relatively few of these were eligible, and that even fewer were young. As Sir Walter Elliot observes in “Persuasion” –

“There certainly were a dreadful multitude of ugly women in Bath; and as for the men! they were infinitely worse. Such scarecrows as the streets were full of! It was evident how little the women were used to the sight of anything tolerable, by the effect which a man of decent appearance produced.”

Many of the eligible young men were of course in the army or navy and away fighting the Napoleonic Wars for much of the time that Jane was living in Bath. And while officers in the services were expected to be at least literate, they came from vary varied educational and social backgrounds. Contrary to popular opinion, although an officer was supposed also to be a “gentleman”, this usually referred to an expectation rather than a predisposition. And often officers fell short of those expectations, which perhaps accounts for Jane’s portrayal of characters like George Wickham, the ne’er-do-well seducer in “Pride and Prejudice.”

I’m sure there were lots of George Wickhams in Bath. It was, and still is, the perfect setting for a novel. It was a place where, given enough money or access to credit, all the trappings of wealth and position could be rented or hired or borrowed for The Season, and where people were often not who they appeared to be. As Jane observed in “Persuasion”

“Sir Walter had at first thought more of London; but Mr Shepherd felt that he could not be trusted in London, and had been skillful enough to dissuade him from it, and make Bath preferred. It was a much safer place for a gentleman in his predicament: he might there be important at comparatively little expense.”

Very few of Jane’s letters survive from her time in Bath and some say that she wrote very little while she was there. Yet it’s well known that Jane was a consummate editor; writing and re-writing, polishing and refining her work until she was satisfied it was good enough. She may well have been working on drafts of her later novels even then. She was certainly observing and remembering what she saw.

We do know that Jane wrote the beginning of her unfinished novel, “The Watsons” while in Bath. Some say it remained unfinished because it was a time of upheaval in her life (with the death of her father). Others believe it so clearly mirrored her own experience (particularly the financial precariousness of the family) at the time that she found it too painful to continue. And perhaps the chapters that she did complete lack some of the refinement and polish of her later novels, yet I find them very poignant and touching. I can’t help thinking that someone of Jane’s intelligence and sensitivity must at times have been hurt by a Society where people were judged so much in terms of title, wealth and appearance; as opposed to their true nature and accomplishments.

In my novel, “AVON STREET” I have tried to explore aspects of the City of Bath that lay hidden and forgotten behind its romantic Georgian image. Jane Austen recognised that all was not always as it seemed in the City. Perhaps it’s little wonder then that she makes such good use of comic irony.

This piece was kindly hosted on the Jane Austen’s World blog on May 11th 2013.